Danielle Arfin

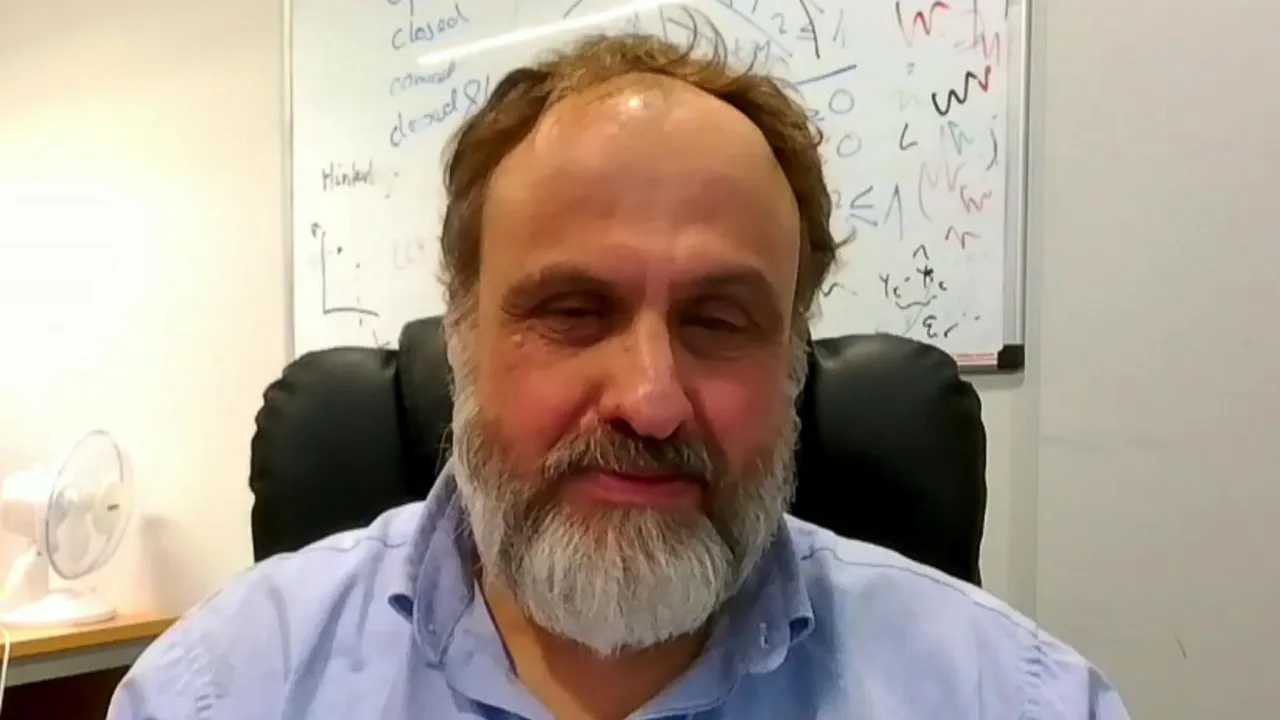

In London this month, more than six hundred scholars and citizens signed a statement titled Standing Against Targeted Harassment of Professor Michael Ben-Gad, condemning what they described as a campaign to intimidate and remove the Israeli-born professor of economics at City, St George’s University. A group calling itself City Action for Palestine had staged noisy demonstrations, circulated a petition on Change.org, and spread accusations on social media branding Ben-Gad, a dual Israeli citizen who, like nearly all Israeli Jews of his generation, completed mandatory military service in the Israel Defense Forces, as a “terrorist” and “war criminal.” According to Jewish News UK, demonstrators gathered outside lecture halls, accused Ben-Gad of “supporting genocide,” and called for his removal based solely on his Israeli citizenship and past military service. The statement supporting him expressed “equal support” for Ben-Gad and the university’s leadership, affirming that “academics and students have a right to go about their work… without facing harassment.”

It is an unambiguous stand for academic freedom. And yet, its 642 signatures are modest when compared to the thousands of Jewish academics who recently endorsed open letters defending Mahmoud Khalil, a Columbia University student whose detention during pro-Palestinian protests sparked widespread outrage. The contrast between the two responses raises a question that cuts to the heart of Jewish life in the academy today. Why do so few Jewish academics speak out when their colleagues are targeted for being Israeli, while so many rally around political causes framed as resistance? The difference may not reflect ideology or conviction so much as the quiet force of fear that now shapes academic life.

The letter defending Khalil was framed as a statement against the “weaponization of antisemitism” and claimed that Jewish identity was being misused to justify repression of pro-Palestinian activism. Its signatories, more than two thousand Jewish faculty, staff, and students, insisted that Khalil’s arrest represented “an assault on academic freedom.” But the letter went further. It suggested that antisemitism itself was being exaggerated or distorted, and that Jewish safety was being invoked to silence dissent. For many, this was a moment to publicly disavow what they saw as misuse of Jewish pain, but for others, it was also a way to distance themselves from Israel and from the social cost of being perceived as aligned with it.

Some Jewish academics signed out of genuine conviction, sincerely believing the petition to be a stand for justice or academic freedom. But even good intentions exist within a climate shaped by fear, where social and professional pressures can narrow the space for independent judgment.

That so many Jewish academics rallied behind a student whose public record included inflammatory rhetoric toward Israel and its supporters was not a sign of shared conviction so much as shared caution. It reflected an environment where opposing the prevailing narrative can brand a scholar as morally suspect, while supporting it guarantees moral acceptance. In that sense, the Khalil petition was not only a political statement but a survival strategy. As The Daily Pennsylvanian reported, more than 2,400 Jewish signatories across campuses, including dozens from Ivy League institutions, described their choice to sign as an act of “solidarity” — a word that, in today’s climate, often doubles as social protection.

Across Western universities, Jewish faculty navigate a fraught landscape where political orthodoxy on Israel and Gaza can feel inescapable. Many privately acknowledge the risk of speaking out against antisemitism or defending Israeli peers. Doing so can result in social isolation, departmental tension, or even professional retaliation. To question slogans like “From the river to the sea” or to condemn harassment of an Israeli professor is, in some circles, to invite accusations of racism or complicity. Silence becomes a kind of self-preservation.

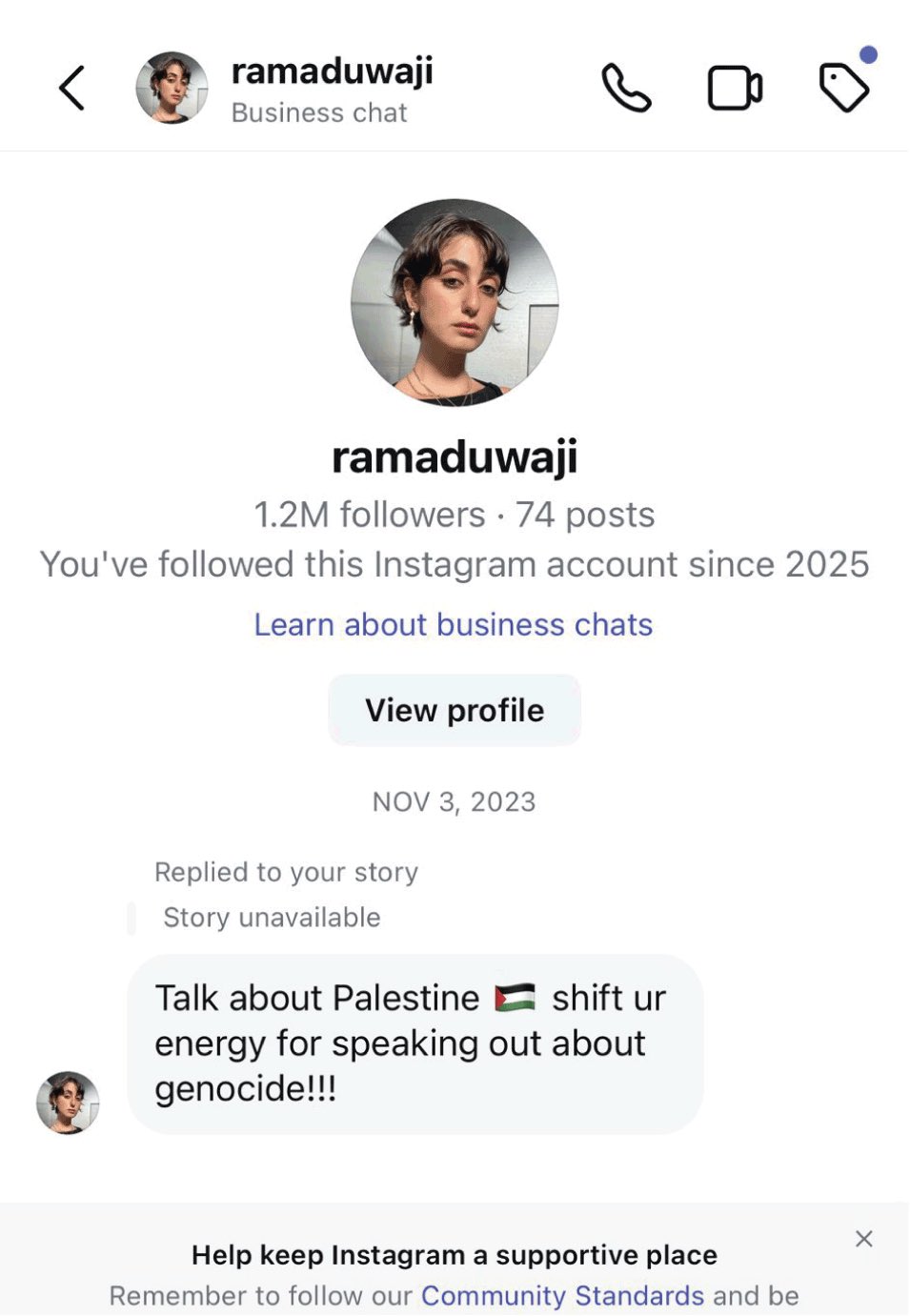

At the same time, a growing number of Jewish academics now publicly align with pro-Palestinian activism as a way of reclaiming moral credibility within institutions that increasingly measure integrity by political conformity. As The Guardian recently noted, younger Jewish Americans, including scholars, are increasingly “renegotiating” their relationship with Israel under pressure from peers and professional networks. What appears to be conviction often masks exhaustion — the fatigue of constantly having to prove one’s belonging.

Signing a petition such as the one supporting Khalil can, by contrast, offer a sense of safety. It signals belonging within a dominant ideological current that defines itself as progressive, humanitarian, and anti-oppression. For Jewish academics already under scrutiny, such gestures can serve as shields, proof that they are not, as some critics crudely phrase it, “the wrong kind” of Jews. It is less about endorsement of every claim within those letters and more about reassurance that one’s professional and social identity remains intact.

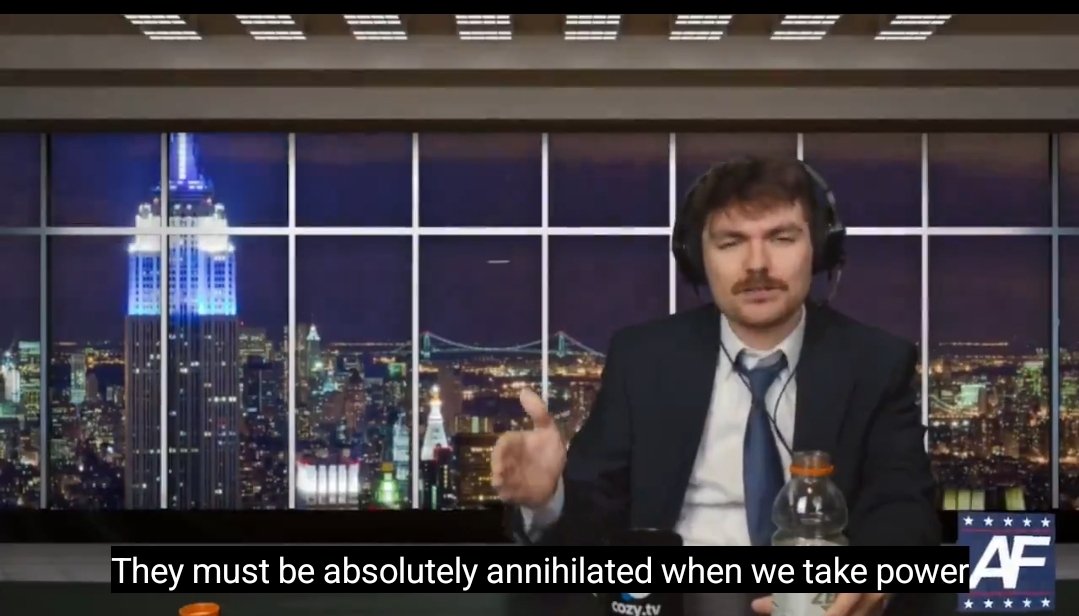

That dynamic carries consequences. When campaigns like the one against Ben-Gad succeed in silencing or isolating Israeli scholars, and when few voices rise to oppose them, a precedent is set that harassment of Jews and Israelis is permissible when framed as activism. The Ben-Gad statement pushes back on that logic, insisting that universities must protect the intellectual and personal freedom of all scholars, regardless of nationality or political association. It is a defense not of Israel’s policies but of the principle that harassment has no place in academia.

To note the disparity in signatures between the Ben-Gad and Khalil petitions is not to shame or accuse anyone. It is to expose a broader reality, that fear has become a structural feature of academic life. Fear of being ostracized, of losing grants or appointments, of derailing careers built within institutions that now see moral courage as reputational risk. Even those who disagree with Ben-Gad’s politics, or with Israel’s actions, should be alarmed at a culture where scholars must calculate whether defending a colleague’s right to exist on campus will end their own.

The silence of Jewish academics is not apathy but survival, and until that changes, fear, not freedom, will define the academy. What is being lost in that silence is more than courage. It is the possibility of truth itself, the willingness to stand for one another when it matters most.